Out today from corona\samizdat and available from their website

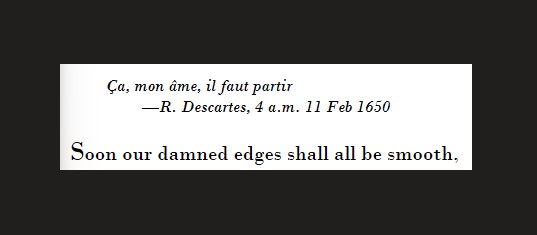

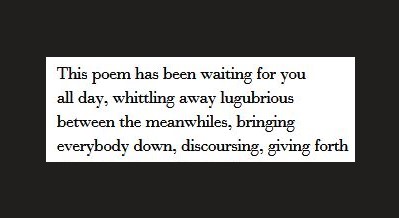

Synopsis: Dr. Ed’s head is spinning: a long-lost ‘son’ has just been sent over to his office by the temp agency, his shopping-addicted wife seems to have disappeared, and the clinical trial that he is running for a revolutionary new anti-depressant might well be going off the rails. But we needn’t worry about Dr. Ed: he is in control of everything, including himself.

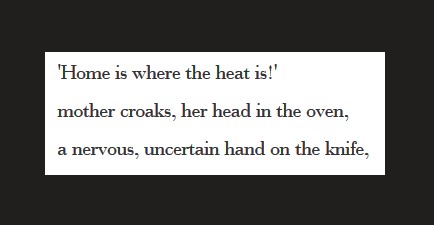

Thus begins Skinner Boxed, the first of two thematically linked novellas that comprise White Mythology. In the second piece, Love’s Alchemy, five narrators deliver stories of betrayal that are nested like Russian dolls, stories that link an attempted seduction in Tokyo in 1987 to a brotherly schism that erupts during a bottle rocket game of ‘war’ in 1970s Massachusetts. From boys who poison their teacher’s plants to men who compulsively urinate into rivers, these strange (and strangely connected) monologues drop the reader into the pitch-black dunk tank of the soul.”

Add it to your “To Read” shelf on Goodreads.com:

…