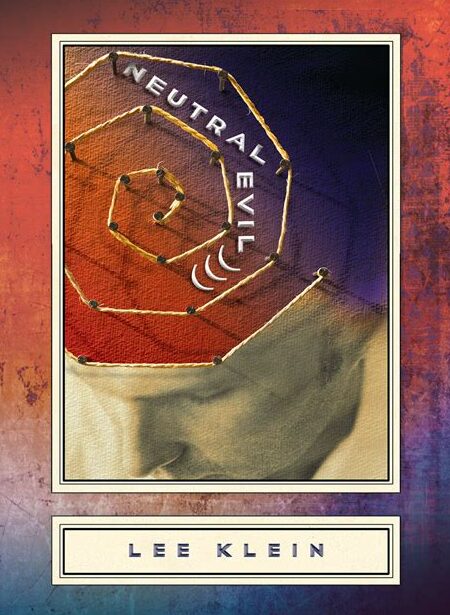

Long after finishing it, I find myself still thinking about this—let’s not call it autofiction—digressive apologia pro vita sua and meditative, measured assessment of self, family, and culture. And, above all, this is not so much an account but a demonstration of how the artist resists the pull of the “neutral evil” of the world by harnessing the chaotic good to be found in it, in his or herself, and in other works of art.

Lee Klein’s subtle, serpentine prose was not quite what I was expecting (the acerbic wit and irony of his earlier book, Thanks and Sorry and Good Luck: Rejection Letters from the Eyeshot Outbox (?)) when I pulled this slim volume from the TBR-soon shelf not as soon after acquiring it as I would have liked—and now, definitely should have done, since if I had done so I would now also have (what I presume is) its sequel, Chaotic Good under my belt and be ready for the forthcoming Like it Matters, too, cos the writing is simply that compelling, I am happy to report.

And this is coming from someone who knew nothing of (and by my track record, likely to care little for) the book’s ostensible subject matter, a concert the monkish drone-metal band Sunn O))). For said concert is simply the scaffolding for the concert-goer’s inner artist to muse most cogently, productively, but unfetteredly (if that’s a word) and (mos def) peripatetically on topics only seemingly disconnected from one another.

Our narrator is simultaneously enraged by the 45th President of the United States and his stooges (“fuck these fucking fucks”) and paranoid about todays (circa 2017) even-more-heightened potential for random violence America seems to have acquired of late (he is always on the lookout for someone to push him onto the subway tracks, or burst into the theatre guns-a-blazing). He is also more than acutely aware of the unappeasably ratchet-like nature of the Weberian ‘Iron Cage’ of instrumental rationality which passes for work of life and the life of work (the reproduction of the means of production)as we fly, to borrow a phrase from the poet Giorgio di Cicco, or are flown ever deeper into this new, and not-so-new century:

The lights are on a timer” is something I have to remember and say every night to [my wife] as a running joke. The regulation of the off-switch on the main front-room light reflects the mechanization of everyday movements required to hold it all together, maintain employment, excel to a degree that ensures autonomy as an individual contributor under a boss who allows me maximum room to make her look good. I don’t get anxious because I’m on top of it all, have my arms around it, the sense that there’s this mass of work I can constrict until it’s a tight little ball in the palm of my hand. The light is on a timer but of course now the days are longer each day. After a while adjustments are required.

If his line of work is somewhat fortunate for all that, the reader cannot but get anxious on his behalf, or feel his unconscious’s own consciousness of anxiety’s background noise, the never sleeping hum of the still-vibrant, postmodern city in a state of some renewal amidst much decline.

Art and family provide bulwarks against all these looming, but never-quite present threats (though they, too can add to the pile, piling-on: a family adventure of going to a distant shopping mall is recounted in enough detail to ensure the reader gives the establishment in question a wide enough berth), and if playing, rather than ‘merely’ listening to and being a fan of, music provides real solace (and, like writing, a sense of mastery, of containing chaos in a “tight little ball in the palm of [one’s] hand), still, along the way to practicing a life-in-art, we encounter much resistance—some external, much internal. It would be a strange artist indeed who did not suffer from the Not-Good-Enough disease, which Klein details toward the end of the book:

Enthusiastic comments from total strangers after I played open mics in Austin meant nothing. The handful of negative comments that stuck with me meant everything since they confirmed my doubts, something I hadn’t encountered yet to a significant degree. In sports, doubts are confirmed by the final score, by the team’s record at the end of the season, by statistics. But this was my first unquantifiable experience out of college. The dragon that had always sat on a pile of imaginary gold pieces inevitably flailed now that it was for real. My response wasn’t to practice every day and night for hours and write better songs and hone what I was doing until the dragon took flight. Instead I rode my bike around and used tip money on pints of beer and saw bands (shows were free at first and then $2 at Emo’s), trying to meet people to play with, hoping to meet women, and instead of doing either for the most part I started writing poems. Alone out at night, drinking beer, I’d write a silly surreal rhyming poem for an alluring woman and then I’d fold it into a paper airplane and throw it toward her table as I left the bar and headed to a show. The novelty and excitement of this led to writing stories.

Freud would have us caught in the middle between the twin poles of Eros and Thanatos, in this context between the delight in creation and the certainty (in our own minds) that we are useless and that our actions and creations pointless, dead on arrival, in advance. We can escape this binary (get out of our own way) only when we can get out of our own heads and learn the art of play by forgetting self and social ties and mores for a spell, a spell of being under the spell of even (or especially) the silly and surreal…

But there is also another impediment to art, much encountered in these pages: another agent of Thanatos in the more slyly sinister form of distraction—in this case, regarding the business of making music, since much of one’s time seems to be spent thinking about the acquisition of or the selling of newer, ever-more enticing accoutrements of the trade: though he says later on that “the goal is to reach the spot where I no longer want anything, much of his discussion of music in these pages charts the minds insistence upon continued wanting—and though he says still later on that he will stay off social media in order to make “a conscious effort to keep to myself for a while,” he nevertheless remains glued to a buy-and-sell app by way of proxy, perhaps, as do we: there’s always a better guitar to be lusted after, pedals to add to the collection or unload, such that even the life-in-art seems riven/driven by the same imperatives that drive us here, to GR and to other social media platforms, the unappeasable desire to desire, and the always-obscure objects of said inchoate or unexpressed-because-inexpressible desires, desires which are always the condensations of and displacements from our ‘real’ desires, whose meaning is always postponed because ever-postpone-able…

…Which is what the form of this clever novella seems to say to me, at least. For all that, however, art and love are the (not exalted, but humble, and all the more important for that) tools of resistance, still—yes, ‘even now’, viz.:

I enter notes into my phone’s Notes app and everyone around me must think I am texting or tweeting, not knowing I’m leaning against the wall entertaining myself, leaving behind a trail of misspelled abstractions to decipher later, breadcrumbs to retrace my thoughts, aware that this could be a novel, as though I’m working on a novel now, conceiving it, recognizing the possibility for one when it appears in the wild, committing once again to fulfilling the need to create text from life and work on it daily and let it sit and work on it and let it sit like bread rising until the dough is ready to cook and consume […] I feel like that Francis Bacon painting I had in my room in high school and college, a hunter or lost hiker in the swirling primary-colored world of a Van Gogh imitation/homage, now also maybe an adequate representation of the individual in the echo chamber, as I lean against the southern wall of the venue’s back bar. I stood in the same spot for Swans over the summer. Soundwaves rippled through the air and I laughed as I held my palm to the vibrating wall.

Every moment of his journey to the end of night provide such occasions for memory, reflection, and then spring-boarding into imaginative play—real, if momentary freedom, even, or especially when that triple-jump seems prima facie negative, as when he claims that all those past years on which he reminisces, “the majority of my life so far, were the inverse progress of a butterfly, bright colors exchanged for the wooly gestative comfort of a cocoon that yields a caterpillar offspring, en route to the larval, pupal form of middle-aged parental existence, the final destination achieved once our Kalibird caterpillar of a child transforms into a butterfly herself.

A beautiful extended metaphor for one kind of beauty, that—the heightened receptiveness to the melancholy, autumnal charm of transitioning from being one of life’s dancers to becoming a member of its audience.

There are also numerous similar passages about listening to music herein, and I’ll give you but two superb examples:

The otherworldly phenomenon of the needle tracking across the grooves at a set speed produces amplified vibrations))), you see beyond the sound you hear, like every song were real, had three-dimensional shape, described experiences that occurred in physical form like anything on TV, and it could be played over and over, unlike television at the time […] I watched the needle track across the record as the cassette wound from the left spool to the right spool, taking it all in, like I was stealing it, getting a discounted version for private portable personal use […]

If there is solace in the transport, here, it is because such transport is the solace, just as metaphor carries us over the border of one reality and into another, potentially more vibrant (lively, or alive?) one, one with its roots in matter but its eyes on something other, by being, at its own root, a thing that carries other things.

Lee Klein shows us, embodies how the humble art of art is done, via memory, dream, reflection—and so often that I can’t resist quoting at least one more example, that of, in which the singer’s

arms are out like a bad kid in my neighborhood when I was growing up who one gray and humid afternoon rode his bike no-handed, fists in the air, mouthing the opening of Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man,” an image burned into my memory, although now the bad kid’s bike seems more like a squadron of amplified Harleys […]The intimidating bad kid in my neighborhood who one afternoon long ago rode his bike with fists in the air acting out the opening of “Iron Man” died young thanks to alcoholism. He lived at home most of his life and littered fifths of cheap vodka in the honeysuckle bushes along the path between our neighborhood and the old village streets. He embodied “Iron Man” in a way he never recovered from, or he was able to convey the spirit of cartoonish evil because as a teenager he was already a Wicker Man aflame inside. Sabbath offered the illusion that straw on fire was heavy metal. Mouthing the lyrics (“heavy boots of lead, I hear voices in my head”) transformed him into Frankenstein’s robot, indestructible, invincible. Music supported him, transformed him, gathered forces and stood at attention behind him. I saw it and believed it.

And now I, as well.

Neutral Evil is available from Sagging Meniscus Press http://saggingmeniscus.com