Years ago, when I was a very lost first year undergrad, I had an inspiring professor named Dr. Tim McNamara (below) who succeeded at the near-impossible: at getting a motley collection of over-worked young engineering students and military cadets to pay attention in a dreaded, required freshman English survey course. The heft of the Norton Anthology of English Literature that we lugged to class along with our Optics, Mechanics and Chemistry texts, combined with the fragility of its 1000+ onion skin pages (as well as with the impenetrable density of its type), cast an ominous pall over the room as we slouched in our chairs awaiting not Infinite Jest, but Infinite Boredom.

But Dr. McNamara won us over immediately. He did so by showing to us why (and how) Chaucer, Spencer, Milton, Donne, et al. were not just some random resinous garden gnomes who somehow stubbornly insisted upon persisting in the junk-yard of history. No sir! They were, rather, living and -yes- breathing distant relatives, the kind of knowing, naughty Uncle Wise Guys who would wink at you even as they declaimed some important weighty truth about the human condition, the uncles who would “playfully” slap you in the face in one of their “pretend” boxing matches, but who would also slip a five dollar bill into your coat pocket while you were looking the other way -a gift you would only discover after the visit had long ended, after you had been shuttled back to the banal perils of quotidian reality.

But Dr. McNamara won us over immediately. He did so by showing to us why (and how) Chaucer, Spencer, Milton, Donne, et al. were not just some random resinous garden gnomes who somehow stubbornly insisted upon persisting in the junk-yard of history. No sir! They were, rather, living and -yes- breathing distant relatives, the kind of knowing, naughty Uncle Wise Guys who would wink at you even as they declaimed some important weighty truth about the human condition, the uncles who would “playfully” slap you in the face in one of their “pretend” boxing matches, but who would also slip a five dollar bill into your coat pocket while you were looking the other way -a gift you would only discover after the visit had long ended, after you had been shuttled back to the banal perils of quotidian reality.

There was always more than a little twinkle in Dr. McNamara’s eyes at the start of what seemed like each & every class. This was when he would intone, like a caffeinated whiskey priest, the name the writer with whom we would be grappling that day, and then pause and stare us down. These pauses were at first just a beat, but became increasingly stentorian (and proportionally hilarious to us callow engineers) as the year wore on. But we also loved what followed the pause, for each new (to us) writer who were going to spend that particular day testing ourselves against, was always, as Dr. McNamara put it, the “best”, “first” or “most” of his or her age, genre or nation. And Dr. McNamara really meant it, but there was also something else, something impishly playful, which told us that we were his nieces and nephews, and that despite our best efforts to evade him, that he’d be giving us a good slap across the face real soon.

Thirty years on, I now forget the who-was-what-and-when, but phrases like “unparalleled observer of human nature”, “greatest stylist of his generation”, and “champion of wit” linger and mutate in my imagination, forming ever-new combinations, but are always anchored by one thing: by the incredible, unforced, but mischievous ardour in his voice: it was a voice characterized above all by a sense of transport, by the enthusiasm* of one who knew the joy of discovering (and then sparring with) the Master. And Tim (as Dr. McNamara soon insisted we call him) was inviting us, just as he himself had been invited, to box. Later on I came to understand that Tim’s approach was kind of analogous to what the philosophers call Kantian aesthetic disinterest**: whether discussing his love of Shakespeare (“simply the greatest writer of all time!” -now that is one that I actually do remember) or asking us about engineering, about our own lives, about our hopes and dreams, Tim seemed, at those moments, to lack an ego: what was superlative or unique about other writers, and about other people in general, was what interested him.

Listening to his lectures you got a sense that Tim was trying, in spite of the odds, to let those writers speak to us unmediated, to gain us access to (to borrow from Milan Kundera) “the one millionth part” of them that makes them separate from the mass of humanity, of that which makes them unique, inimitable, of that which makes their art theirs and theirs alone. It’s a very modernist notion: the idea that artists must forge a unique, individual style, that artists are “at war” with clichés of all kinds, that it is human particularity that keeps us awake and alive as readers, as writers . . . and I am well aware of just how unfashionable, in academic circles at least, that idea has been in the past few decades. But what I’ll be doing here in subsequent posts is following in what my imagination chooses to remember as the footsteps of my first mentor, Dr. Tim: I’ll be looking closely at the work of some writers I admire, writers who, if they share anything at all in common, it is a fascinated, avuncular mistrust in the protean nature of a world into which they, like their characters, find themselves thrown -writers whose literary innovations are a fully human response to the increasingly inhuman competition in what Milan Kundera in a slightly different but related context called “the trap that the world has become”. If so, we can only hope that we have inherited our uncles’ and aunts’ best gambits. For we conduct our lives in a whirlwind: call it “late”, “transnational” or “neo-liberal” capitalism; call it modernity; in any case our existence is predicated upon forces of ever-accelerating centripetal movement, and it has been ever since at least the late 18C, just when the novel also started coming into its own. Ours is a world distinguished by “constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social relations, everlasting uncertainty and agitation”, where “all that is solid melts into air“, and where we, like the artist, are compelled to innovate, summoned by an imperative to keep pace.

But whether human nature either bends or breaks under such pressure is a question that writers of fiction are in a better position to ask than are the political or literary theorists, for, as I see it, one of the things fiction can do for us better than theory is to dunk our imaginations into a full-on sensory immersion acid bath -or, to mix my metaphors, into punching ourselves sufficiently awake that we can attempt to confront this ever-shifting “reality”. Socio-economic and cultural vectors are fired at us just as they are launched at an author’s characters from all angles, and we, readers and writers, vicariously participate in lives that can be as formed by as much as tested by them. And we scrimmage most regularly with those writers who most make us feel or think something new, something we didn’t feel or think before.

Milan Kundera actually claims that novels that fail “to uncover a hitherto unknown segment of existence [are] immoral.” I’m not sure I would go that far, but I do know that novels that fail to try to tease something new out of existence – and, inextricably, out of language – are downright boring. And so in the entries that follow I will be attempting to grapple with the work of a number of late 20C writers who themselves try to Quixotically joust with the whirlwind. If my method is to read these works “as if” writing them -that is, to try to unpack them and see how they were put together- it may become apparent to some readers that I tend to favour writing that breaks from some or many of the conventions of realism: writing that might prompt an “As IF!” response from readers expecting those conventions to be followed. There has been much debate about this over the past ten years or so in the American literary press -debate centred on what James Wood called “hysterical realism” in the “sociological” fiction of the “bastard children of Charles Dickens” (writers such as Thomas Pynchon, Don Delillo and even Zadie Smith). This debate had been sparked, in part, by a 1996 article Jonathan Franzen wrote in Harpers concerning the apparently bleak future for fiction: entitled “Perchance To Dream”, Franzen asked whether the experimental novel retained any cultural relevance today. I suppose that the entries in this blog will attempt to comprehend that question more fully, if mostly indirectly.

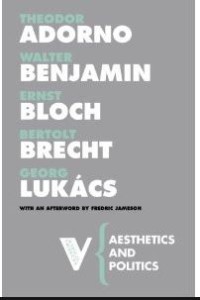

It is an old debate, however. Earlier in the past century it was one that famously centred on two heavyweights of literature: the playwright Bertolt Brecht and the Literary Critic Georg Lukacs.

It would be nice to return to that specific text sometime. But first I am going with my gut with two opening gambits: first, to some short stories by T.C. Boyle, and then to Milan Kundera’s aesthetic meditations in The Art of the Novel. But I will close this first sortie with a passage from Brecht:

Methods become exhausted; stimuli no longer work. New problems appear and demand new methods. Reality changes; in order to represent it, modes of representation must also change. Nothing comes from nothing; the new comes from the old, but that is why it is new [. . .] If we wish to have a living and combative literature, which is fully engaged with reality and fully grasps reality, a truly popular literature, we must keep step with the rapid development of reality.

Postscript: I haven’t spoken with Dr. Tim since taking his class, but I write this as if still, in some sense, his student, with an eye looking out not so much for paternal approval as an avuncular bang on the ear.

*Enthusiasmos (Gk) – from enthous ‘possessed by a god’ – COED

**Aesthetic disinterest may seem cold and detached, but it isn’t neutral. From the indifference of the object to the disinterest of the subject – or from the former’s superfluous self-exhibition to the latter’s ungrounded reception – the experience of beauty is one of distance and separation. This distance is not a mere absence; it is something positively felt. When I contemplate something that I consider beautiful, I am moved precisely by that something’s separation from me, its exemption from the categories I would apply to it. This is why beauty is a lure, drawing me out of myself and teasing me out of thought. Aesthetic experience is a kind of communication without communion – Steven Saviro, “Without Criteria: Kant and Whitehead” 10.

I had a similar lecturer for Literature years ago… he would wander in absent-mindedly, lower his glasses and say: ‘You’re not third year.’ No, we’re first year. ‘Oh. There goes that preparation. What are we reading?’ Then he’d pause and launch us all into a different world. To this day my appreciation of all the arts comes from those journeys…

Yes, I’m with you here. You’ve painted the doorway rather well.