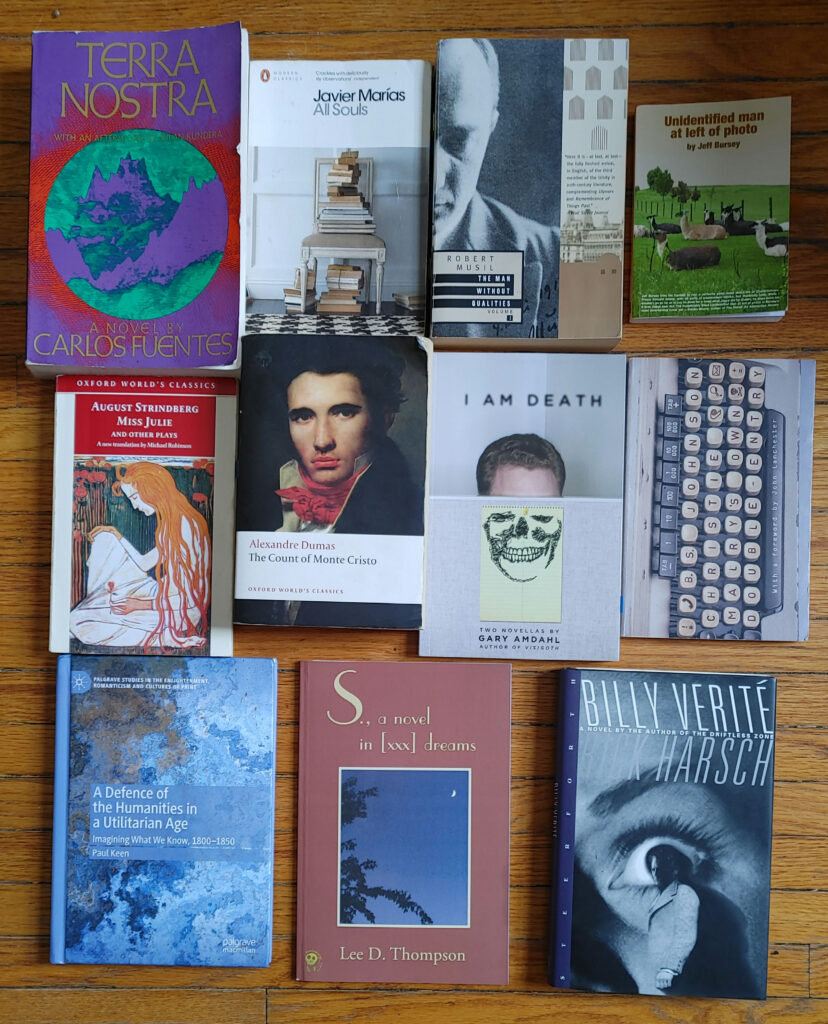

Though my project of reading the long 18th century in chronological order largely flat-lined in 2022 (first because of the invasion od Ukraine—see readings referenced at the very bottom of this post—and then because of what was for nearly a month a mysterious illness—see July-August), all in all the year was a still great one for modern and contemporary fiction for me, the highlights (and one very, very low-light) are gathered here, in order of their reading.

January: Billy Verite by Rick Harsch

While I admired the heck out of Mr. Harsch’s debut novel, The Driftless Zone: Or, A Novel Concerning The Selective Outmigration From Small Cities, this one, his sophomore effort, was simply evidence of the parthenogenetic Master adding still more to his palette: whilst opting to restrict himself to a tightly-plotted form, the author still manages to invent himself into a delicious tizzy of a straitjacket, with the kind of imaginative abandon that you might more properly find in a Rabelais or Laurence Sterne (or Jean Paul [Richter], whose Maria Wutz not only resembles this volume in terms of sheer, demiurgic play, it was to 2021 what this book already is to 2022 for me: a head-over-heels favourite), a submerged, enshackled Houdini, if you will.

Now this was a riot. I laughed, I cried. I literally fell into cliché. I lie, but the truth is in here somewhere, and I will say this: a spoonful of the ol’ sugar-sugar helps the meta-sin stay down (typed as if with gentle effect, as he’s a reader’s kind of writer all along), but seriously how can you not love this (only seemingly) unserious unliterary Guy Fawkes of a guy?

Billy Verité himself (like rogue cops Torgeson and Stratton) is a carry-over from that first novel, but by no means must you read it before this one, and Billy’s bizzarro, genius-level idiot-savant adventures and schemings on an island in the Mississippi (just west of La Crosse, Wisconsin), not only make him a Robinson-Crusoe-meets-Piggy-from-Lord-of-the-Flies-meets-Steve-Buscemi-from-Fargo, but also make this novel worth the price of admission alone.

And, much like that Remington guy from the 70s who liked his razor so much he bought the company, I so admired the heck out the chapter which introduces baddie Skunk Lane Forhension I got permission from the Dude to put it here on my blog, so yeah, as always caveat lector, etc., cos I know the author from the interwebs, etc., etc…

But still—the following tiny tidbit of typically Rabelaisean Noir will give you but a hint of the dee-lights you are in for with this, the second volume of Harsch’s Driftless Trilogy:

“You’re either a fine woman or I’m still drunk. Or dreaming.”

“I think both.”

“Which both?”

June: S., a novel in [xxx] dreams by Lee D. Thompson

In his essay “The Triggering Town,” poet Richard Hugo wisely points out that the reader does not need to know what town this is, much less what part of town, so long as the author is absolutely certain of it. He then goes on to demonstrate the power which inheres in such an assured, assertive stance by quoting from one of his own poems, which begins (as if in a dream), “That silo, filled with chorus girls and grain…”

As we all know, much does depend / upon / a red wheel /barrow, of course, but even more depends upon that “that” there, above: it situates the uncertain reader with confident aplomb in a highly specific place, an equivocating, manic-repressive silo, as determined to bring anarchic energy to your nights as it is to pretend to be only its sweet cornpone (notso) l’il elf by day.

The poem continues:

That silo, filled with chorus girls and grain burned down last night and grew back tall. The grain escaped to the river. The girls ran crying to the moon. When we knock, the metal gives a hollow ring—

Well, in S, author Lee D. Thompson gives us [xxx] (actually more than 30, I counted) very confidently-situated, but interlinked silos which revolve around lost lover, S., who may (or may not?) also be “you” and which may dart back and forth across the ocean, but are always rooted firmly in one “town,” Mr. Thompson’s poetic memory (as Milan Kundera calls that haunting, almost claustrophobic, obsessive aspect of eros, which jealously guards the tower of the soul with moat-and-drawbridge and giant portals, even if the inside of the castle is strewn with garbage and is open to the wind and the rain, its all treasure, no map, and the whole point is the hunt…)

Where was I, again? Oh yes, inside the author’s dreamlife. Or what he remembers of it. And/or has made up about it, as if smashing all the windows in the tower and then carefully, in fine detail, turning each shard to a stained glass still life, then hurling each shard at the white wall of the page for the reader to deal with, to pry from that wall and somehow examine with or without cutting themselves…

And this reader, though feeling shoved into a disorienting silo at first, was unhappy to see the end of this slim volume, and if I could find a flaw to carp about here, it’s just perhaps that I’d like more please, sir. “It takes years of practice” to artistically read/write one’s own dreams, but making (non)sense of others’? I’m only beginning to catch glimpses of S, “You,” and “I” before each “dives into the pool, goes under, vanishes” on me. Maybe that’s the point, I’m left as bereft, bothered and bewildered as the haunted author, as those siloes that all burned down and, though they grew back again, never quite the same way.

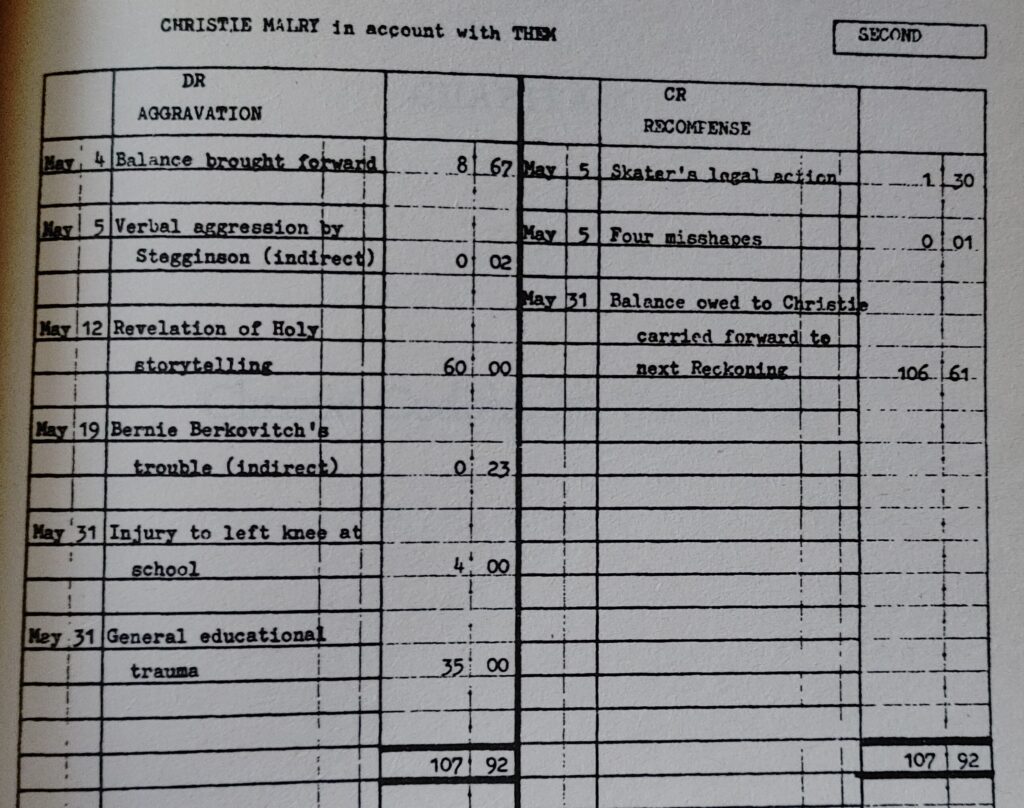

July: Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry by B.S. Johnson (1973)

Christie is a lowly bookkeeping clerk toiling away at a bank, when he decides to take revenge on, well, everyone, by hoisting us with our own capitalist petard, the double-entry bookkeeping system of accounting, for all of the debits (owing to him) we have accrued in his accounting. Hilarious.

Hilarious, too are the many, many many times are we reminded of how our conventional, readerly desires are going to be smashed in this book:

‘My son : I have for the purposes of this novel been your mother for the past eighteen years and five months to the day if I assume your conception to have taken place after midnight. Now that you have had your Great Idea and are set upon your life’s work there is nothing further for me to do [in these pages].

(27)

Or:

Again, I have often read and heard said, many readers apparently prefer to imagine characters for themselves. That is what draws them to the novel, that it stimulates their imagination! Imagining my characters, indeed! Investing them with characteristics quite unknown to me, or even at variance with such description as I have given! Making Christie fair when I might have him dark, for an instance, a girl when I have shown he is a man? What writer can compete with the reader’s imagination!

(51)

—Well, he does flatter us, but this is one writer whose imagination is sure as hell in the running.

July August: I Am Death (2008), by Gary Amdahl

In the waning days of July I began the menacingly funny yet somehow-poignant first novella in this book, the titular “I Am Death,” and got about 26 pages in before running through all the first person conjugations of the verb “to be” myself, then temporarily abandoning the book, along with all other reading (not to mention all other activities requiring any kind of effort whatsoever) while my body spent most of its days and nights trying to figure out just who or what was menacing it.

30 days of a 101.5F fever and 7 days of IV antibiotics later, this is the first book I returned to when reading finally and mercifully returned to me, and, Lyme Disease finally not only confirmed but also slowly healing, I devoured the thing as quickly as a slow reader whose lips involuntarily move as the eyes follow the bouncing ball of the text can possibly read, finishing the confident, always-swerving fading-mobsters meet faded-journo tale “I Am Death” relatively quickly before getting completely bowled over by and obessed with and immersed in the truly miraculous “Peasants” in the second two-thirds of this wonderfully inventive, constantly surprising book.

By “surprising” I mean BOTH on the sentence-by-sentence level as well as that of the plot: this reader was always more or less on edge, on a ledge, hedging his bets as to what would happen, or be said, next (the best possible state for any reader to be in IMHO). “Peasants” concerns the micro- and macro-aggressions that take place in the modern office setting in spite of (or perhaps because of) the ever-watchful traffick cops in HR. So much human potential (not to mention frailty), yoked to the profit margin and ever-beset by that ineluctable modality of the Org Chart, leads to much hilarity, and certain tragedy, as it happens. Just brilliant stuff and one of the best things I’ve read in a long, long, LONG while.

A Potential-Conflict-of-interest Klaxon sounds in my imagination as I type out the words MY VERY HIGHEST RECOMMENDATION (never remembering if there are two “Cs” in “recommendation” but never quite forgetting that there are two “Gs” in “bugger off” either), but not really: sure I have gotten to know the author a l’il bit (albeit on the Twitter) just before and whilst reading this book, but I never ever give a glowing review (or, usually, any review at all) to a book I didn’t truly love. If you’re not the kind of reader to trust the NYT, the Washington Post, the LA Times, or the Chicago Tribune (y’know, the dreaded “media”), please, at least this one time, trust mewhen I tell you, cos halle-bloody-lujah it’s no longer just the Lyme disease talking here, but yer old more-or-less reliable, if virtual pal Dubyedee as well: Gary Amdahl is the real deal, my friends. Read him!

—n.b., since reading I Am Death I have read and have devoted an entire blog post to) another of Mr. Amdahl’s books, The Intimidator Still Lives in Our Hearts. Also amazing, though I reserved this end-of-year review to one book per author 🙂

Some tidbits from I Am Death:

It was the kind of ridiculously far-fetched coincidence that you had to expect, after all, in what was in effect a small town, but find hard to believe in a work of fiction

[At the Jimmy Buffet concert]Things, of course, had changed in America, but because those changes had been concurrent with Rasmussen’s disappearance into middle age, he had not noticed them.

[The new boss]everyone seemed to feel the same way—ashamed at the lengths to which they had gone to be amused—and had adopted the same method of coping—fraternity house levels of intoxication—but this kind of mass self-deceit seemed only to be undoing their ability to remain amused: there was a dangerous current of hostility running though every exchange of favourite song lyrics or bottle of Buffett Beer. In this way it was no different than a stock-car race or football game or election or war: one was there to support the ream; and the team in turn assuaged the superficial loneliness and underlying, almost infrastructural fear of metastasizing anomie that was the cross every white wealthy Christian had to bear, and that sometimes was used in place of a spine.

[Anita]presented herself as an ambitious kindergarten teacher and revealed nothing of herself in conversation. She was very much a machine of the gods, Rasmussen suggested, asking his friends if he might be forgiven for turning the phrase around, raised up and set in place by a kind of invisible corporate crane to the large-gestured wailing and moaning of the chorus, who did not have the slightest idea what to say to her otherwise.

had been trying to read what business school graduates were reading, the more popular and readable essays on management, and it turned out, she told Rasmussen, to be the same old shit: uniformity of product, minimal production costs, and market predictability. Rasmussen, in the course of a life of playwriting, bookselling, arts reviewing, and repeated failure to be extraordinary and unconstrained by reality in his pursuit of beauty and truth, had seen the learned playboys of publishing become Wal-Mart suppliers, had seen the festering corpse of Broadway reanimated by Mouseketeers running a protection racket, and philosophy become marketing, and so could think that he had fallen asleep only because he worked for a software manufacturer who was so successful he could run a press as he might a kennel of Lhasa apsos, as pets, because he liked the breed. We didn’t have to make a profit, he told Anita, so we were free to be ridiculous.

“We published a couple good books,” Anita reminded him.

“They can’t take that away from us,” Rasmussen agreed.

“Your days are numbered, though. You know that, don’t you?”

“I see that they are numbered. I may choose not to accept the figure. “

“What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know. “

“Content will be provided by offshore content providers and coded by trained coders so that it can be poured without spilling into a funnel on one side of our designers’ computers, which will poop books out the other side. From a nozzle. They will be soft at first, but will harden into books.” Anita began to cry and laugh at the same time in a kind of competition. “Oh, they hate me, they hate me, they just fucking hate me, Walter! They know I know how to do what they do, and how long it takes to do it, and they will never ever forgive me.” She stopped suddenly and covered her mouth. Her eyes widened. “No,” she said, “you know what it is? I am The Woman Who Knew Too Much. I am the only loose end of the perfect crime. They are going to have to kill me.”

And finally, and most deliciously:

He was ashamed of himself. He knew the furnace in his brain—not the organ but the thinking—ran on fear, but what he was afraid of he could not say, Was he afraid to say? It was possible. Was he afraid to know? That was much more likely. If he knew, he would say so. He was not so afraid that he could not say what he knew. But could he know? Did he know? He could know if he wanted to, but he was afraid to know. Which meant he knew but was afraid to say. He was a coward of the worst sort: he could not face himself. It made just enough sense to sicken him, to make him feel like someone had a fist in his guts and was squeezing his diaphragm. Was he afraid of losing his job? It was contemptible to think so, and yet . . . had he not just said it? By saying it did he now not know it? Was his job contemptible, and his fearlessness demonstrated by his contempt for it? Or was he contemptible and his fear demonstrated by that very same contempt. Yes, it was certainly all childish and petty—but was not the childish negotiation of petty grievance the primary mode of behavior in the United States of America? Was it not the fundamental means of social and political intercourse? Were not the winners, the rulers, simply men and women who had grown up enough to manage the playground? Were not the losers and the ruled those who simply charged about the playground performing fuming little dramas—He said this and I said that and then he said something else and I smashed him to the ground—about the unfairness of life and the extraordinariness of the stories they had to tell?

June–August: The Count of Monte Cristo (1846), by Alexandre Dumas

This is pretty much the perfect 19C novel, methinks. It’s up there with Middlemarch and Bleak House for me, all equally accomplished in rather different ways, but all also three of the tallest peaks in the mountain range that is nineteenth century realism.

So, I won’t say much about its many, many delicious sub-plots and digressive longueurs here, but I will say that I failed to find an even adequate film or televisual adaptation to treat myself to after I finished (as is my want with many of such bricks, one of the best of which is the relatively recent BBC adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House.

Not that I expected much of the 2004 film version of The Count starring Jim Caviezel and Guy Pearce (below, left). It was actually the more satisfying of the two I attempted, with a very good portrayal of Dante’s years in the prison-fortress of the Chateau D’If, but playing fast and loose with the plot otherwise.

I don’t even know where to begin listing the failings of the Gerard Depardieu adaptation from 1998 (above, centre), so I won’t. I abandoned the series halfway through the first feature-length episode. This book deserved (and deserves, c’mon BBC, etc.!) so, so much better… [n.b. someone on Twitter referred me to the animated 2004 version, Gankutsuou (above, right), which I have yet to see…]

September: Miss Julie and Other Plays (1887–1907), by August Strindberg

I could have made this entry about Henrik Ibsen’s Four Major Plays or Anton Chekhov’s Five Plays, since for me September was a month of spent gap-filling by reading 19C dramas that I’d somehow failed to read previously. So I choose Strindberg here, partially because as much as I loved those other two playwrights (and partially because I already have made a blog post—sort of!—”out of” Chekhov, in that I “wrote” a pastiche Samuel Beckett play using Chekhov’s own words, in the order they appear in Five Plays), mostly I loved Strindberg just that bit more. Or rather, I fell head-over-heels, completely in love with the hatred so artfully on display in one specific play of his in that volume, The Father. Anyhow, here’s what I thought about each of the plays, presented here (as well as in the Oxford edition) chronologically:

The Father (1887)

Connubial contraflow mendacity + misogyny + misandry = a clearly masterful, near miraculous miasma of misanthropy from which there can be no escape. Strindberg needed just the right amount of insanity…

DOCTOR. But it’s possible his mind may be disturbed in some other way. Please, go on.

LAURA. That’s just what we’re afraid of. You see, he sometimes has the most peculiar ideas, to which as a scientist he might of course be entitled if they didn’t threaten the well-being of his entire family. For example, he has a mania for buying ll manner of things.

DOCTOR. That’s worrying; what kind of things?

LAURA. Books! Whole crates of them, that he never reads.

…to imagineer this out of nada-ville, and achieves a perfect balancing act here. 6 gobsmacked stars out of 5.

Miss Julie (1888)

You’ve seen this all before (these class and gender wars)

What kind of a spectacle is this on a Sunday morning?

((though to be fair late 19C Europe hadn’t, or overmuch)) … but in for me a ho-hum, journeyman 3*

The Dance Of Death (1900)

Precisely like Bergman’s “newly dead dancing across the hills” (as Bruce Cockburn once sang) in The Seventh Seal…

…except minus all traces of love or humanity, i.e. minus the Knight and the Squire and the martyred girl and the fortunate circus family. Only the murderous, avaricious defrocked priest remains, except he’s also the lifeless, life-denying pastor from Fanny and Alexander who’s now married not to F&A’s widowed actress-mother, but a female version of himself (also an actress), who when you so much as blink is now the antimatter version of the superannuated hero of Wild Strawberries after he and all the berries are long, long dead. It’s the six-hour-long Scenes from a Marriage though the clock sez less than two, and where what’s done is done and cannot be undone, to bed, to bed, to bed, but the dream contains just another couple of bad actors in a musical medley of Beckett’s Happy Daze/Endgame, except both trashcan Sinatras hum the “March of the Boyars” as they go to war with each other, animus vs anima, except this psychomachia is just all to the tune of me me me me me, maestro.

4*

A Dream Play (1901)

WT unholy F was that?!

—Random snippets of dialogue from the sanitorium restaurant of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain shouted out while “The Blue Danube Waltz” played in the background?

—An Oxford Union debate between the faculties of Law, Theology, Philosophy and Medicineheld in the common room of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest?

—Some automatic writing passed back-and-forth between of W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory whilst Mme. Blavatsky held a séance & channeling the battling spirits of a Stockholm borgmästare, Emile Zola, and the Krishna of the Mahabarata?

—The source documents for T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land sung to the tune of “Being For the Benefit of Mr. Kite”?

—A good/bad acid trip (assuming there is a difference) taken while a comunity theatre stages Bulwer Lytton in your mother’s pristine, antimaccassar- and plastic-seat-cover-bedecked, unlivable living room and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome plays on the 70″ TV mounted above the electric “fireplace” behind them?

Exhibit A:

OFFICER. Oh, this is dreadful, really dreadful!

SCHOOLMASTER. Yes, dreadful, that’s precisely what it is when a big boy like you has no ambition…

OFFICER. [pained]. A big boy, yes, I am big, much bigger than them; I’m grown up. I’ve finished school… [as if waking up] but I’ve a doctorate… What am I doing sitting here? Haven’t I got my doctorate?

SCHOOLMASTER. Yes, of course, but you’ll sit here and mature, you see, mature… Isn’t that it?

[Redacted, to spare your sanity]SCHOOLMASTER. No, you are still far from mature…OFFICER. But how long will I have to sit here, then?

SCHOOLMASTER. How long? Do you think that time and space exist?… Suppose that time exists, you ought to be able to say what time is. What is time?

OFFICER. Time?… [Considers] I can’t say, but I know what it is. Ergo* I know what two times

two is, without being able to say it.—Can you tell me what time is, sir?SCHOOLMASTER. […] Time?— — —Let me see! [Remains standing motionless with his finger to his nose] While we are talking, time flies. Therefore time is something that flies while I talk!

A BOY [getting up]. You are talking now, and while you are talking, I’m flying, therefore I am time! [Flees]

SCHOOLMASTER. According to the laws of logic that is perfectly correct!

OFFICER. But in that case the laws of logic are absurd, because Nils can’t be time just because he flew away!

SCHOOLMASTER. That is also perfectly correct according to the laws of logic, although it remains quite absurd.

OFFICER. Then logic is absurd!

SCHOOLMASTER. It really looks that way. But if logic is absurd, then so is the whole world too… and in that case why the hell should I sit here teaching all of you such absurdities!—If someone will stand us a drink, we’ll go for a swim!

Exhibit B:

LORD CHANCELLOR. What was hidden behind the door?

GLAZIER. I can’t see anything.

LORD CHANCELLOR. He can’t see anything! No, I can believe it!— — —Deans! What was hidden behind the door?

DEAN OF THEOLOGY. Nothing! That is the solution to the riddle of the universe!— — —In the beginning God created heaven and earth out of nothing.

DEAN OF PHILOSOPHY. Nothing will come of nothing.

DEAN OF MEDICINE. Rubbish! That’s all nothing!

DEAN OF LAW. I have my doubts!… There is a fraud here somewhere. I appeal to all right-thinking people!

DAUGHTER [to the POET ]. Who are these right-thinking people?

POET. If only one could say! It usually means just the one person. Today it’s I and mine, tomorrow it’s you and yours.—You are appointed to the post, or rather, you appoint yourself.

And so by all the powers which the heyday of European imperialism and the approaching assasination of Franz Ferdinand have invested in me, I hereby appoint myself to bestow upon this…this “play”…

5*/0*/No Rating

Ghost Sonata (1907)

Brilliant stuff, and to my mind what happened when S. imposed a bit more…structure, shall we say (or apparent structure at least), on the possibilities opened up by the genius-level-cray-cray of A Dream Play six years earlier. Would LOVE to see this one staged, along with The Father,

ALL IN ALL, then: A one-of-a kind of his kind**

(the most wonderful thing about Tiggers, natch)

**I saved this bit from the OUP Introduction for those who made it this far, cos, to be quite honest, I don’t think I would have made it through the 300++ pages of this text if I had stumbled upon this passage on Strindberg’s “reaction” to Nietzsche in the introduction first:

October: Unidentified Man at Left of Photo (2020), by Jeff Bursey

Meta- and fan- tastic

Early on in his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, post-modern author Milan Kundera playfully warns us credulous readers:

It would be senseless for the author to try to convince the reader that his characters once actually lived. They were not born of a mother’s womb; they were born of a stimulating phrase or two or from a basic situation. Tomas was born of the saying “Einmal ist keinmal.” Tereza was born of the rumbling of a stomach.

We impressionable ingenues persist in believing in these characters, of course, in spite of such warnings, and not in spite of but because of ourselves: we believe in Anna Karenina, or Tomas and Tereza, because (as MK also notes) in our imaginations our own lives are structured like novels: life mirrors art.

Well, what kind of life must it be, then, which is mirrored in Canadian (Atlantic Canadian to boot) author*** Jeff Bursey’s Unidentified Man at Left of Picture, as detonative a tome as a narratologist ever dreamed of, let alone read with as much pleasure as this jejune (not jeune) reader did?

For Mr. Bursey takes Milan Kundera’s dictum and rubs it in our face like a character in a Brecht play parading about up and down the aisles with a sandwich board before, after, and, most ‘inappropriately’, during each and every g-d scene—breaking down that fourth wall over and over and over again, trampling into a fine dust that wafer-thin sheetrock or drywall separating ‘us’ from all that ‘art’, and kicking up said dust until it permeates the very air we breathe. I lost track of how many times Mr. Bursey invaded my head-space to urge me to be less of a readin’ rube, but I dogeared over 50 pages of the (to me, delightful, as I reveled in watching JB put a slightly different spin on it each time he did so) stuff—a select few of which are recorded in the reading notes below

(below? Who the hell knows where anything even is anymore. Not only is Jeff Bursey destroying the book as we know and love it, GR itself is determined to nuke the whole GR experience with its monstrously bloated—and yet short on actual detail—’book page’.)

Yes he tries his best, Mr. Bursey does, to take all the innocent-funfunfun (identifying-with-the-characters, suffering-with-their-sufferings, falling-in-love-with-their-fallings-in-love…) out of reading, doesn’t he? He wants our fun to be next-level-fun, meta-fun, watching him having fun making fun of our childish desire for naïve narrativity, incentivized Identikit innocence. Or since (due to all the powers not invested in me by the Intentional Fallacy) I can never know what Jeff Bursey himself wants, his narrator does anyway. His narrator’s the Daddy wants to take the T-bird away.

He tries and, well, he succeeds, mostly. Cos I still found myself identifying with his characters of course, even if their surnames were MicmacMann or Mackendolanyon or MacMackMick. Or Blushwicker, living in a town called Breadalbane, waiting for a fictional-world-ending hurricane named Bruce.

You know where JB doesn’t succeed, though? He gets the hurricane’s name and gender and year that it wipes out C-town (as Prince Edward Island’s capital city, Charlottetown is called) completely wrong. Also the wiping-out part! Cos Hurricane Fiona (or Fredna, or Fidelia or something) just barreled through the region a couple weeks back, destroying all kinds of stuff (especially on Mr. Bursey’s home turf of Newfoundland, rather tellingly I’d say), but those Cs* in C-town are pretty much all OK (though some rural folks still without power!). Even the dope-fiend kids at the local high school are all right, even though this book gives them a pretty good pummeling, too. Not sure how the poets are doing, though. The poets had their doors blown off by Hurricane Jeff in these pages, just before Bruce swept in to finish them off… But, yeah, in the prediction racket UMALOP is surely no match for The Farmer’s Almanac—minus 0.5 stars there**!—but in the Meta- racket though? Metacognition, Metaethics, all the metatalk (especially metabasis, so committed to a plurality of PEI personas is our author, erm, ‘narrator’, rather), UMALOP has cornered the MicMacMarket.

I’m just rambling now, so time to sum-up. You know what? I was a genuine fan of Mr. Bursey’s first novel, Verbatim: A Novel, the pleasures of which are as austere and as rigorously administered as could be imagined, since they only escape out of the straight-jacketted corset of their chosen form (the novel is a collection of speeches made in provincial parliament by the official documentarian of government proceedings, Hansard) in suppressed and repressed and oppressed sighs, so to speak.

This novel is that one’s true, apposite-opposite, or perverse-obverse: Mr. Bursey not only strips away the corset and straitjacket here, he lets the inmates out of the asylum to run riot all over this Cuckoo’s Nest of an Island—UMALOP is truly an unbridled, yet affectionate Horatian satire of Island Life.

As for we sublunary readers, on the other hand…well, if we have changed places with said lunatics, if we have, in our persistence in believing in and living by fiction(s), then at least Mr. Bursey’s post- post- modern meta-meta-scrivenings is a call to reveille (t’is ‘one work that wakes’, poet G.M. Hopkins’ review of it sez) which has taught us how to sing—and laugh—along with our scourging:

Our revels now have ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

*Charleses and Charlottes, of course. The sort of filth you were imagining, dear reader, wouldn’t go down well in polite C-town…

** Plus a loud, snobbish raspberry for influencer JB’s shameless plugging of and shilling for Tim Hortons and Timothy’s World Café in these pages, both of which serve but the nominus umbra of a true cuppa (a Baudrillardian simulacrum of the Ontological Argument for Coffee, Anattākaffee, in other words, words words) in this Great Steropticon of a ‘novel’. —As Descartes once said of Galileo, the franchisees (not to mention and the purveyors of all things CanLit****) have built without foundation.

***Jeff is not only a friend I have made on the internet), he is also published by the same umbrageous Verlaghaus/complotmenting cotierie (corona\samizdat) as myself, so please feel free to see this review in as jaundiced or as rosy a light as befits your own temperament (Sanguine, Choleric, & c.) and as your predisposed tolerancy permits (“What rhubarb or senna shall scour these scribblerians hence?” a certain GR personality once wrote, albeit in a preliminary draught…) or charity towards such rodomontado narrischkeit as all this might allow.

****Mix&Match columns to suit, season with the passing seasons to taste*****

(entire travesty available here).

*****Mr. Bursey’s fiction is None Of The Above, praise be!

May–October: The Man Without Qualities, Vol. 1 (1930), by Robert Musil

I have actually finished everything published in Musil’s lifetime as well as the postumously published material in Volume 2, leaving 300pp. or so of alternate drafts and sketches to get through before actually finishing this monumental 1774-page set.

But with a half-dozen or so unbelievable metaphors on well-nigh every page (only some of my underlinings and dog-ear-ings of which I’ve collected over here), this book left me breathless. I purchased that other, hardcover two-volume slipcase edition this summer cos I underlined so much in this paperback edition, it’s—pretty much all underlining now!

One of my most inspiring professors in uni (who taught the full-year Joyce-Beckett course) once told us that his bedtime reading was always a re-read of either of Joyce’s Ulysses or Proust’s ISOLT, one after the other, in perpetuum. I’d argue that this one could hold up to endless, repeated re-readings too, and never get exhausted (tho I just might) of insight, or of surprise.

I’ll leave you with a mad-lib of sorts, Musil as Nostradamus for late Oct., 2023:

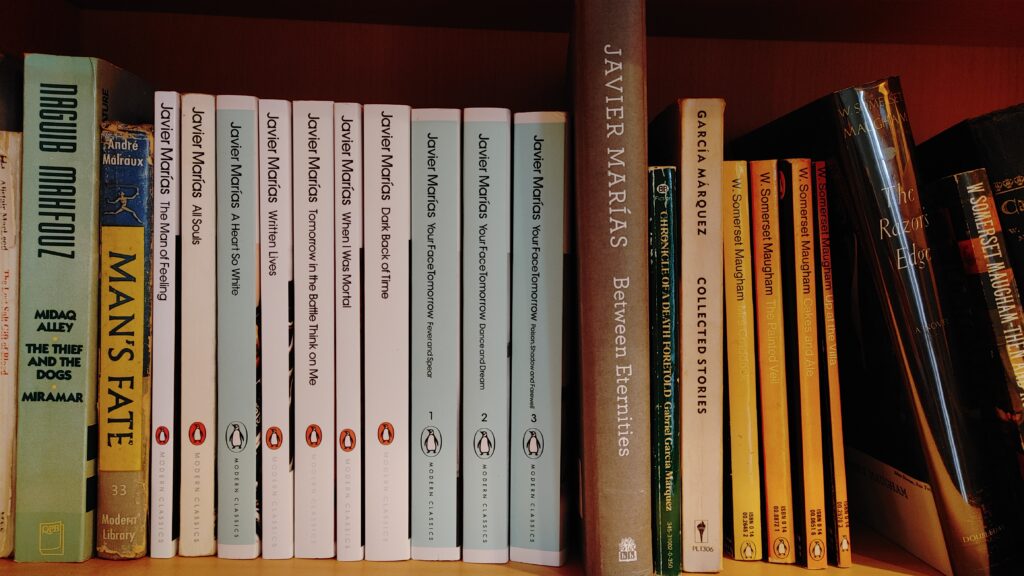

November: All Souls (1989) by Javier Marias

This was a first JM read for me, and I fell instantly in love with his sentences, his indirection, his meanders***.

I won’t say too much, as to describe this one really would be to spoil it, as though hardly anything happens, the way it doesn’t happen unfolds in just the most delightful way possible, in that way that makes something happen in you.

So, instead I will make one claim, and then leave you with two evidentiary, epitomic quotations (if you like them at all, you will love this novel).

One Claim:

Just as Joyce’s [book:A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man|7588] forever closes-off the hell-fire Roman Catholic sermon for all future writers in every human settlement the galaxy over, early on in this novel, Marias fully-completely puts paid to any other novelist’s burnin’ yearnin’ to portray an Oxford High Table dinner in all its pomposity/spleandour/mendacity/ flirtatiousness/triviality/hilarity. Finis, done. Fuggedaboudit.

Two Exemplary Quotations:

And I enjoyed the great consolation (or perhaps even the immense pleasure) of proposing the impossible and knowing that it would be rejected: for it is precisely the recognition that it is impossible and the certainty of rejection – a rejection that the person who proposes the impossible and takes the floor first in fact expects – that allows one to hold nothing back, to be vehement and more confident in expressing one’s desires than if there were the slightest risk of their being satisfied.

[…] And I was surprised to find myself daring to say (much too early in the conversation) things I hadn’t even foreseen myself saying or was even sure I wanted to say, either at the beginning or perhaps even at the end (the word “together”, the word “son”, the word “stepson”), but I thought, too, that my last sentences, including the very last, had been acceptable within the narrow range of possible varieties of behaviour in non-blood relationships. Now it was Clare’s turn to be surprised, at least a little, although, inevitably, her surprise was only a pretence. But her pretence took the form of not being surprised, which is one way of handing back the surprise (or its pretence) to the other side.

***I have since bought ten (!) more books of JM’s already. If ever you find yourself that way inclined, do seek out the handsome Penguin Modern Classics Editions. They just feel right somehow.

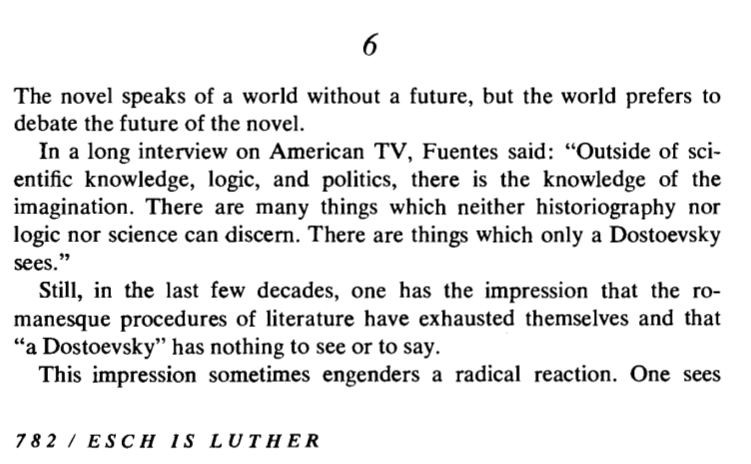

December: Terra Nostra (1975) by Carlos Fuentes

It will take several re-readings of this novel (and/or possibly likely several eternally-present lifetimes) before I can even imagine saying anything about any of what follows—from the novel’s Afterword, by Milan Kundera:

Post-script: Nonfiction in 2022

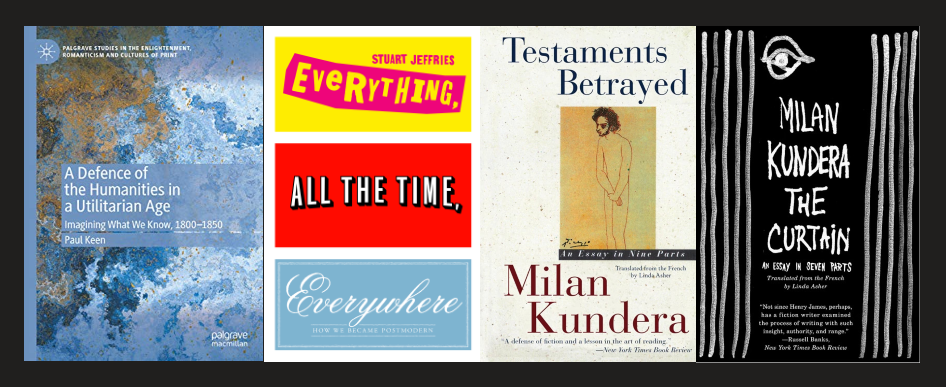

Two of the four nonfiction books which I enjoyed the most were both works of literary or more specifically, cultural criticism: Paul Keen’s A Defence of the Humanities in a Utilitarian Age: Imagining What We Know 1800-1850 (Palgrave, 2020), and Stuart Jeffries’ Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern (Verso, 2021).

And while I have already written a review of Jeffries’ book here on my blog, I am in the middle of writing an extended “Appreciation” (not quite a “gloss” what I’d call a “digested read”, but longer than a review) of the Keen book as I type this, and shall amend this post accordingly when finished.

The other two books I loved (re-reading for the third time) were works of “author-criticism” by Milan Kundera, Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts (1993) and The Curtain: An Essay in Seven Parts (2005)—and which I am writing extended and in-depth “Digested Reads” of in 2023…(with the former coming in January I hope…stay tuned!

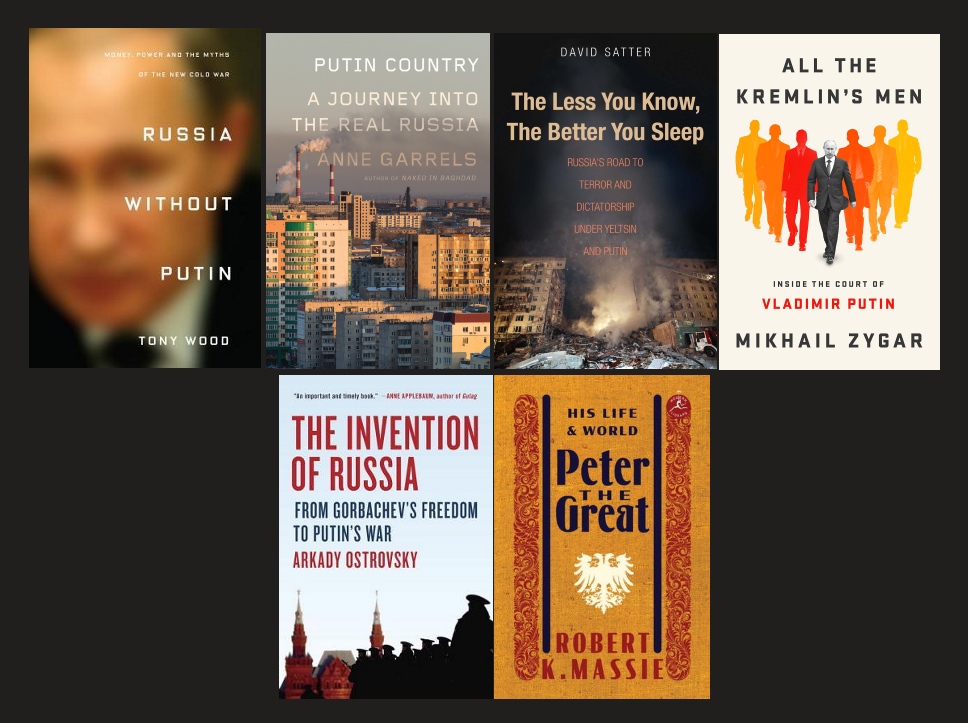

I also read and took a lot of notes on a clutch of books on (mostly) contemporary Russia, for an “primer” article I hope(d) to write on the subject…That got shelved when I became afflicted with Lyme this summer, but perhaps I’ll find the time to return to it, not sure.

But they are all well worth reading, and I’ll link my brief reviews to them here:

- Russia Without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War (Verso, 2018) by Tony Wood

- Putin Country: A Journey into the Real Russia (FSG, 2016) by Anne Garrels

- The Less You Know, the Better You Sleep: Russia’s Road to Terror and Dictatorship under Yeltsin and Putin (Yale, 2016) by David Satter

- All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin (PublicAffairs, 2016) by Mikhail Zygar

- The Invention of Russia: From Gorbachev’s Freedom to Putin’s War (Viking, 2016) by Arkady Ostrovsky

- Peter the Great: His Life and World (Modern Library, 2012) by Robert K Massie

Finally

My least favourite read was the book pamphlet on Lyme Disease, It’s Not Just Ticks It’s Not Just Lyme: Pertinent insights into the origins, recognition and treatment of Lyme and related infections

It’s not just that its so overpriced.

It’s not that it’s so short.

It’s just not that helpful!